This multi agency guidance is designed to set out a framework for partner agencies within the Bury Safeguarding Adults Board (SAB) to work together to manage cases involving individuals who are at high risk of significant harm and/or death due to self-neglect, lifestyle choice and/or refusal of services.

RELATED CHAPTERS

RELEVANT INFORMATION

Self-neglect at a Glance (SCIE)

Working with People who Self-Neglect (Research in Practice)

Ten Top Tips when Working with Adults who Hoard (Community Care)

August 2024: This guidance which contains detailed information for practitioners on working with self-neglect and hoarding – including how to respond- was added to the procedures site.

This page contains an accessible, formatted version of the Self Neglect and Hoarding Policy. Alternatively you can view a PDF version here.

CONTENTS

1. Introduction

The Care and Support Statutory Guidance refers to self-neglect as covering a wide range of behaviour, including a person neglecting to care for their personal hygiene, health or surroundings, as well as behaviour such as hoarding.

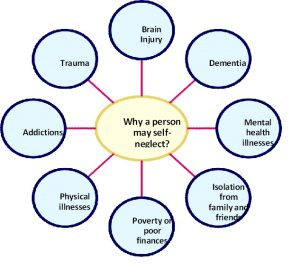

Self-neglect can occur as a result of a person experiencing poor physical or mental health, brain injury, trauma, addictions, poverty, isolation from family and friends or dementia. They can become physically unable to care for themselves or the environment they live in. There may be situations where practitioners identify serious concerns when an adult refuses the support of services, but is viewed to be at great risk and they may need to be safeguarded through statutory interventions.

Safeguarding duties apply to an adult who:

- Has care and support needs and;

- Is experiencing, or at risk of, abuse or neglect and;

- As a result of these care and support needs, is unable to safeguard themselves from either the risk of, or the experience of abuse or neglect, including significant harm (see Safeguarding: What it it and Why Does it Matter?)

Working with people who are self-neglecting can be challenging, but working in collaboration with others, sharing information, ideas and analysis will not only achieve better outcomes for the individual but will enhance practice and provide much needed support for the practitioners.

This guidance aims to to help practitioners to identify and respond to people who are at risk of harm due to self-neglect and should be read in conjunction with:

- The Care and Support Statutory Guidance – self-neglect is included as a category under adult safeguarding.

- Article 8 of the Human Rights Act 1998 gives a right to respect for private and family life. However, this is not an absolute right and there may be justification to override it, for example, protection of health, prevention of crime, protection of the rights and freedoms of

- Mental Health Act (2007) s.135 if a person is believed to have a mental disorder and they are living alone and unable to care for themselves, a magistrate’s court can authorise entry to remove them to a place of safety.

- Mental Capacity Act (2005) s. 16(2) (a) the Court of Protection has the power to make an order regarding a decision on behalf of an individual. The Court’s decision about the welfare of an individual who is self-neglecting may include allowing access to assess capacity.

- Public Health Act (1984) 31-32 local authority environmental health could use powers to clean and disinfect premises but only for the prevention of infectious diseases.

- The Housing Act 1988 a landlord may have grounds to evict a tenant due to breaches of the tenancy agreement.

2. What is Self-Neglect?

Self-neglect is an extreme lack of self-care to the extent that it threatens personal health and safety. It is sometimes associated with hoarding and may be a result of other issues such as addictions and mental health illness. It is important to try to and engage with the person, to offer support without causing further distress, and to understand the limitations to our interventions if the person does not wish to engage.

2.1 Why do people self-neglect?

(Click on the image to enlarge it)

(Click on the image to enlarge it)

| Mental health illnesses can include | Physical illnesses can affect certain abilities |

| Depression | Energy levels |

| Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | Attention span |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) | Organisational skills |

| Hoarding disorder | Motivation |

| Anxiety | Memory |

| Personality disorders | Confidence |

| Mood disorders | Decision making |

| Psychotic disorders | Sleep |

| Bereavement | Side effects of medication e.g. drowsiness |

2.1 Recognising self neglect

Social and community factors:

- Declining family or community support;

- Isolating themselves from friends and family;

- Lack of interest or concern about life;

- Unwilling to attend appointments including medical or housing appointments;

- Refusing to allow services to access the property, for example staff working for utility companies;

- Repeated episodes of anti- social behaviour, either as a victim or alleged person causing the issues;

- Declines support from health and social care.

Personal neglect

- Inattention to personal hygiene including sores/ulcers with poor healing, dirty hair, skin and nails;

- Malnutrition or dehydration including, overeating, undereating, making poor diet choices, lack of food available in the home;

- Declining or refusing prescribed medication and or other health care:

- Diabetes- refusing insulin or treatment of leg ulcers;

- Inability or unwillingness to take medication or treat illness or injury;

- Refusal of equipment such as pressure relieving tools and mobility aids;

- Absence of needed dentures, eyeglasses, hearing aids, walkers, wheelchairs, braces, or a commode.

- Alcohol/ substance misuse – which does not always mean addiction;

- Poor financial management for example bills not being paid leading to utilities being cut of Build-up of debt;

- Inability to avoid self-harm.

Neglect in the home

- Living in unsanitary conditions;

- Human or animal faeces not disposed of;

- Presence of vermin;

- No running water, sanitation, plumbing or working toilet;

- Major repairs are needed and not addressed;

- Unsafe living conditions. Lack of utilities e.g. electricity, gas and poor maintenance;

- Lack of heating. Using candles, which can pose a fire risk. Hazardous wiring or electronic items;

- Hoarding, unable to part with things that no longer have a need or a use such as magazines, broken items, letters, cans, clothing etc. The amount of clutter interferes with everyday living, for example if the person is unable to use their kitchen or bathroom and cannot access room;

- Fire risks for example escape routes blocked by hoarding;

- Inadequate housing or homelessness;

- Fire risks linked to unsafe smoking habits;

- Keeping a large number of pets and inability to care for them adequately.

3. Providing Multi Agency Support to Someone who may be Self-Neglecting

The Care Act 2014 made integration, cooperation and partnership a legal requirement for local authorities, and all agencies involved in public care. However, responsibility for managing risks does not rest on the shoulders of one person. This is a complex area of work, and it is vital that practitioners feel supported through collaboration with others. Seek out others who are working with or know the adult. Working in collaboration is essential if adults are to be offered the range of support they require in a timely manner.

Multi-agency working is about providing a seamless response to individuals with multiple and complex needs. This could be as part of a multidisciplinary team or on an ad hoc basis. Roles and responsibilities, the different structures and governance of colleagues from other sectors need to be understood. Working across organisational boundaries is critical to planning and providing appropriate support.

Multi agency working enables earlier intervention, which is the best way to prevent, reduce or delay needs for care and support and safeguard adults at risk from abuse or neglect.

Things to consider in a multi-agency approach:

- Include other agencies and organisations at all points of support.

- Who else is involved?

- Who needs to be involved?

- What information is held by others and/or is required?

Cooperation and consistent engagement between agencies is important to help reduce the risk of adults slipping through the system and tackling self-neglect at an early stage or preventing it from happening in the first place. It makes it possible to see the whole picture, facilitating:

- Early effective risk identification;

- Improved information sharing;

- Joint decision making.

If a referral is received and there is not enough information for you to support the adult, the referrer should be contacted to see if there is any additional information available, even if anecdotal. Pick up the phone and or meet face to face. This is the best form of communication when you need to get information quickly.

Find out from the adult who has supported them in the past. Is there anyone who has previously built a good relationship?

Effective multi-agency working can be time-consuming and can lead to differences of opinion (see Multi Agency Escalation Process). It is essential to enable different parts of the jigsaw of knowledge to come together. It is key to reducing risk and gaining the best outcomes for the person.

When making referrals into other agencies, see what support they may have put in place; Speak with partners about overcoming barriers and sharing learning.

It is important to work with the adult until all the risks have been identified and shared with the multi-agency group and documented, and the risk mitigation plan has been implemented, as far as is practicable. When working with people in relation to hoarding and self neglect, relationship building does take time.

Low level self-neglect may contribute to an adult being harmed or even death. Tenacity is essential when working with adults who are self-neglecting and non-engaging. Success is more likely to be achieved if the multi-agency group identifies one key person who can establish some rapport with the adult. The person who has the best rapport with the adult should have regular touch points with them.

3.1 Making Safeguarding Personal

See also Making Safeguarding Personal.

The adult should always be at the centre of their care and support. The process should be led by the them, and they should be informed every step of the way where appropriate in line with the Making Safeguarding Personal approach. Form a relationship and start conversations to get to know the person rather than immediately focusing on the issues. People who self-neglect can find it difficult to engage with agencies.

Keep persevering, take time to build a trusting relationship, and keep communication consistent. It is important to understand what outcomes the adult wants, and what they would like from any support or intervention. Empowering the adult to help themselves will have the best long-term affect. Studies have shown that short term interventions such as blitzing a home can be very traumatic. Long term support, where the person guides what support and interventions they have, is most effective. The person should be treated as an individual. Processes are not a one-size fits all.

3.1 Key principles

Understand the person’s background, it may be possible to identify underlying causes that help to address the issue. Explain your role and what you can offer within your role and what you may ask others to offer.

- Be non-judgmental – everyone is different;

- Treat the person with respect and dignity;

- Listen to them and work with them to help themselves;

- Explore alternatives, fear of change may be an issue so explaining that there are alternative ways forward may encourage the person to engage;

- Be mindful of fluctuating capacity (see also Section 10, Assessing Mental Capacity and Recognising Fluctuating Capacity);

- Provide reassurance, the person may fear losing control, it is important to allay such fears.

- Always go back – regular, encouraging engagement and gentle persistence may help with progress and risk management.

- The Mental Capacity Act must be well understood and implemented in the context of self-neglect. If you are not able to carry out a mental capacity assessment, contact a health or social care representative for help (see Mental Capacity chapter).

- If the adult is assessed as not having mental capacity, and decisions are being made in their best interests – this must be explained to them (unless sharing the detail is not in their best interests).

- A clear record is made of interventions and, decisions and rationale.

- If the adult is making unwise decisions, that is their choice – but every effort should be made to explain to them the likely consequences of not addressing ongoing risks that result from their decisions.

- Relationship-building work and time for long-term work is supported.

- Pressure from others (agencies/family/neighbours/media) needs to be managed.

- Reflective supervision and support are a good way for staff dealing with people who self- neglect to help them understand the complexities of this area of work, the possibilities for intervention and the limitations.

- Practitioners are able to consider options for providing long term engagement and support.

- Overcoming self-neglect can be a very daunting task for an adult. It is important to not overwhelm them; break things down into small steps to make them achievable. It is also important to understand what the adult finds achievable and come to a compromise with them.

- Mostly, remember, there is no one model of intervention for self-neglect. Each person, their story and symptoms of self-neglect will differ.

3.2 Tips for starting a conversations

Building a relationship and trust takes time, to start this you need to have an initial conversation:

| Ask the person to tell you a story about them or their past. | Take a note of objects around them such as photographs and jewellery and engage conversations about specific items. | Find out what the adult wants help with, this may not be related to their self neglect. |

| Find out information about the person’s past and how this may trigger their behaviour in the present. | Have an open and honest conversation and ensure their response has been acknowledged. | Look into the person’s support networks including friends and family. Find out any interests they may have or had previously. |

| Set milestones, keeping them small. For example, ask ‘what hopes do you have for the coming week’? | Ensure you display empathy.

Write down some key points before having the conversation. |

Identify the person’s strengths, so you can highlight these during conversations, and have some ideas about how they might draw on these strengths. |

| Consider ‘If this person was my friend, how would I speak to them?’ | Offer an understanding statement for example, ‘I understand that the problem with your neighbours is really affecting you’. | Ask ‘What are your current concerns’? |

| Go at the person’s own pace. | Ensure you are in a location where the person feels comfortable to talk, which may not always be at home initially. | Be clear about what can happen next. |

| Ask them what they would like to accomplish in the future. | Ask them what they would like to work on together, and what they want to achieve. | Appreciate their circumstances and tell them you want to learn about them, ask about their strengths, abilities and preferences. |

| Encourage a deeper conversation for example, ‘What are the things working well in your life?’ | Ask them ‘What helps you when things get difficult?’ | Body language – don’t look shocked or uncomfortable, be open and positive, be mindful of your facial expression. |

3.3 Think Family

Self-neglect by adult family members can often adversely affect whole households. Consider the impact the person’s behaviour has on other family members (including children and informal carers). If there are any concerns about a child you must share concerns with children’s Social care (see Greater Manchester Safeguarding Children procedures).

In order to support families to make changes that are helpful and long lasting, work needs to be done with all the members of the family. Recognising that the needs and desired outcomes of each person in the family affect each other, will support and enable sustainable change (see The Whole Family Approach). Family means different things to different people. We know that different communities and cultures consider family in a different way, and this is not static. The understanding and practice of family changes and develops over time and is affected by external circumstances and environments.

- What impact is the person’s behaviour having on the people around them?

- What impact are other people in the family having on the person self-neglecting?

- Is there anyone else at risk, should a referral be made to children’s social care?

- Is domestic abuse involved, and should a MARAC referral be made?

Risks that have an impact on other people will need to be addressed, with or without the cooperation of the person who is self-neglecting if they ate not engaging. It is still paramount that all activity is communicated to the person.

Consider engaging community, friends, and family, but be mindful that it could be the family who triggered any trauma. Speak to neighbours or any one the adult may interact with.

Are there any voluntary/community organisations who could offer support?

3.4 Professional curiosity

See also Professional Curiosity chapter.

Professional curiosity is about having an interest in adults and their lives rather than making assumptions. Curious professionals engage with individuals and families through conversations, observations and asking questions to gather historical and current information.

Professional curiosity is central to working with people who are self-neglecting and non-engaging. Safeguarding Adult Reviews have highlighted many aspects of this, including the importance of carrying out home visits rather than always inviting people into the surgery or office, especially when there are concerns of possible of self -neglect. Being respectfully nosey will lead to a much better understanding of the adult’s lived experience.

Seek advice if you do not have a good understanding of the law that can be used in relation to self-neglect.

Tips for professional curiosity:

| Offer to make a cup of tea, whilst doing so see if there is enough food in the cupboards and fridge. | Ask to see where they sleep, is it easy to access, are the sleeping arrangements appropriate for that person? | Ask if they feel safe living where they are, if they say ‘no’ explore why. |

| Find out how they keep themselves warm. Discuss heating arrangements. | Give the person time to answer the question. Allow for silence when they are thinking. | Never make assumptions without talking to the individual or fully exploring the case. |

| Use your communication skills: review records, record accurately, check facts and feedback to the people you are working with and for. | Focus on the need, voice and the lived experience of the person. | Listen to people who speak on behalf of the adult and who have important knowledge about them. |

| Speak your observations such as ‘I’ve noticed you’ve lost weight, have you been feeling unwell? | Pay as much attention to how people look and behave as to what they say. | Build the foundation with the person before asking more personal and difficult questions. |

| Ask ‘How are you coping at the moment?’, ‘What helps when you are not feeling your best?’ | Explore the person’s concerns. Don’t be afraid of asking why they feel a certain way. | Put together the information you receive and weigh up details from a range of sources and/or practitioners. |

| Ask yourself ‘How confident am I that I have sufficient information to base my judgements on?’ | Question smoking habits, and consider fire risk at the same time such as ‘Where in the property do you smoke the most? Is it in bed or the living room?’ | Speak to the person about medications. Ask if they are taking medication and how they find it. Do they have side effects are they taking it consistently? |

| Ask who visits and how long it has been since they had a visitor. | Ask if they are in any pain, and what they are doing to manage the pain? | Ensure the person feels listened to and valued.

When ending the conversation, thank them for sharing with you. |

4. Common Challenges when Offering Support

Adults who self-neglect or who are at risk of self-neglect may:

- be isolated.

- decline help that is offered to them.

- be reluctant to engage with professionals.

- have compromised or fluctuating mental capacity.

- have mental capacity, but make unwise decisions.

- find it difficult to trust.

- be wary of statutory services.

- not realise the extent of harm they could cause to themselves.

- have rapport with a practitioner from one agency –e.g. a housing officer, a community and voluntary sector worker, but this input is not known about by other agencies.

- minimise need and risk.

- withdraw from agencies, while continuing to be at risk of significant or serious harm,

- have chaotic lifestyles and multiple or competing needs.

- misuse substances and the underlining self-neglect being overlooked.

- have children, or have had the children removed.

- cause environmental harm and neighbours complaining about anti-social behaviour.

Challenges for professionals include:

- being unclear about each other’s roles and responsibilities.

- silo working and not sharing information or update with other agencies.

- being unclear about the extent of their legal powers to intervene, to mitigate risk and to improve the person’s situation.

- self-neglect cases are often ones that involve a significant level of risk.

- cases that do not require a formal safeguarding response are sometimes not progressed proactively.

- communication between everyone involved with this person is key to creating a shared narrative.

- poor multi-agency working and lack of information sharing and communication;

- lack of engagement from the individual or family.

- challenges presented by the individual or family making it difficult for professionals to work with the adult to minimise risk.

- an individual in a household being identified as a carer without a clear understanding of what their role This can lead to assumptions that support is being provided when it is not.

5. Key Considerations

Do you have concerns? Is someone you are supporting showing signs of self-neglect that causes you concern?

If yes, have you spoken to the adult about why you are there to see them, what their desired outcomes are and what you can offer to support them?

(If you haven’t spoken to them, please see the guidance in Making Safeguarding Personal and ensure the adult’s views and needs are the centre of the support).

Next – Speak to other agencies, are you aware of who else is involved? If not, find out which other agencies are working with the adult and contact them immediately. They may hold vital details you require to offer full support. Consider setting up a Team Around the Person Meeting.

Find out who else is in the household or part of the person’s network? Consider who can offer non-professional support.

Children – If there are children living in the home, consider a referral to the Children’s Safeguarding Team.

Vulnerabilities -Is the adult vulnerable, do they live with a mental health condition or learning disability? If yes, consider the Mental Health Act 1983, and ensure you have spoken with a healthcare contact about the best way to offer support.

Mental capacity – Does the adult have mental capacity at the present time? If you have concerns about the person’s mental capacity speak with a health or social care professional for support or to carry out a mental capacity assessment. If the person does not have mental capacity, decisions can be made by other people to keep them safe if this is in their best interests. Even if the person does not have mental capacity, their views and wants should be taken into consideration. See also Mental Capacity chapter.

Advocacy – Does the person require an independent advocate? Are they aware that they are entitled to an advocate? The local authority has an advocacy duty if the person has care and support needs or are the subject of a safeguarding enquiry. See Independent Advocacy for more details.

Risk – Is the person causing a risk to the environment and is this affecting other people? Under the Environmental Protection Act 1990 or Public Health Act, the local authority may have a duty to intervene and clean the environment. This may provide temporary improvements, but it can also be traumatic for the individual. This should be carried out with care and long term support. Even if the local authority duties do not apply, continue to support the person to improve their situation. Don’t walk away. If you still have concerns, walk alongside to support them in making decisions in their best interests.

Safeguarding – Have you sought assistance through the safeguarding procedures? If not, speak to your manager for advice, or contact the council to make a safeguarding adults referral.

6. Hoarding and Fire Risks

6.1 General characteristics of hoarding

Between 2-5% of the population are thought to hoard although there is no apparent link between age, gender, ethnicity, education, socio-economic status, occupational history, tenure type and hoarding behaviour. However, in Bury those who hoard in council properties are significantly older than the average population. This is a common trend as those who are younger often have their hoarding behaviour controlled by those they live with such as parents or a partner, thus preventing that behaviour coming to the attention of services.

Long considered to be a form of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), hoarding disorder was reclassified in the 2013 as a condition in its own right. Some people with OCD hoard for very specific obsessive worries or fears, so it is important that health professionals correctly assess if a person’s hoarding problem is because of OCD, or as a result of hoarding disorder.

6.2 What is hoarding?

Hoarding is the excessive collection and retention of any material to the point that it impedes day to day functioning. Pathological or compulsive hoarding is a specific type of behaviour characterised by:

- Acquiring and failing to throw out a large number of items that would appear to hold little or no value and would be considered rubbish by other people.

- Severe ‘cluttering’ of the person’s home so that it is no longer able to function as a viable living space.

- Significant distress or impairment of work or social life.

When a person’s hoarding behaviour poses a serious risk to their health and safety, intervention will be required. With the exception of statutory requirements, any intervention or action proposed must be carried out with the person’s consent. In extreme cases of hoarding behaviour, the very nature of the environment should lead professionals to question whether the person has mental capacity to consent to the proposed action or intervention and should trigger a mental capacity assessment. (see also Section 10, Assessing Mental Capacity and Recognising Fluctuating Capacity)

Hoarding poses a significant risk to both the people living in the hoarded property and those living nearby. Those staying at the property will face the same risks to their mental and physical health as the hoarder. This is a serious concern where children or vulnerable adults are staying with the hoarder. A child or young person growing up in a hoarded property can have their development put at risk and in some cases lead to the neglect, which is a safeguarding issue.

The needs of the child at risk must come first, and a Safeguarding Children referral should be made (see Greater Manchester Safeguarding Children procedures).

The increased risk of fire at the hoarder’s property also poses a risk to neighbours especially in high-rise towers or blocks of flats. Where a hoarded property is identified, regardless of the risk rating (see Section 7, Clutter Ratings and Guidance for Practitioners), adults should be advised of the increased risk and a safe exit route identified. Gas and electric safety checks may not have been completed due to an inability to access parts of the property. Appropriate professional fire safety advice must be sought. This will allow crews to respond appropriately. Fire services can provide support and guidance as well as fire safety equipment and should be part of the multi-agency response. See Home Fire Safety Assessments (Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service for more information).

6.3 Types of hoarding

Object hoarding- includes:

- Compulsive acquiring

- Saving

- Disorganisation

This is the most common form of hoarding, and could consist of one type of object or a collection of a mixture of objects such as old clothes, newspapers, food, containers or papers.

Animal hoarding- Involves the obsessive collecting of animals, often with an inability to provide minimal standards of care. Any kind of animal can be accumulated by people who hoard, including cats, dogs, rabbits, ferrets, birds, guinea pigs, and farm animals. The hoarder is unable to recognise that the animals are or may be at risk because they feel they are saving them. In addition to an inability to care for the animals in the home, people who hoard animals are often unable to take care of themselves. The homes of animal hoarders are often eventually destroyed by the accumulation of animal faeces and infestation by insects. This type of hoarding is on the increase.

According to the Hoarding of Animals Research Consortium, animal hoarding is the pathological accumulation of animals meeting the following criteria:

- Having more than the typical number of companion

- Failing to provide even minimal standards of nutrition, sanitation, shelter, and veterinary

- Denial of the inability to provide this minimum care, and the impact of that failure on the animals, the household, and human occupants of the dwelling.

- Persistence, despite this failure, in accumulating and controlling.

(Click on the image to increase the size).

Any evidence of animal hoarding should also be reported to the RSPCA.

Data hoarding – is a more recent type of hoarding. There is little research on this area, and it may not seem as significant as object and animal hoarding, however people who hoard data could still present with same issues that are symptomatic of hoarding. Data hoarding could present with the storage of data collection equipment such as computers, electronic storage devices or paper. A need to store copies of emails, and other information in an electronic format.

6.4 Why do people hoard?

Fear and anxiety: compulsive hoarding may have started as a learnt behaviour or follow a significant event such as bereavement.

Long term behaviour pattern: possibly developed over many years, or decades, of “buy and drop”. Collecting and saving, with an inability to throw away items without experiencing fear and anxiety.

Excessive attachment to possessions: people who hoard may hold an inappropriate emotional attachment to items.

Indecisiveness: people who hoard struggle with the decision to discard items that are no longer necessary, including rubbish.

Unrelenting standards: people who hoard will often find faults with others, require others to perform to excellence while struggling to organise themselves and complete daily living tasks.

Socially isolated: people who hoard will typically alienate family and friends and may be embarrassed to have visitors. They may refuse home visits from professionals, in favour of office based appointments.

Large number of pets: people who hoard may have a large number of animals that can be a source of complaints by neighbours. They may be a self-confessed “rescuer of strays”

Mentally competent: people who hoard are typically able to make decisions that are not related to the hoarding.

Extreme clutter: hoarding behaviour may prevent several or all the rooms of a person property from being used for its intended purpose.

Churning: hoarding behaviour can involve moving items from one part a person’s property to another, without ever discarding anything.

Self-Care: a person who hoards may appear unkempt and dishevelled, due to lack of toileting or washing facilities in their home. However, some people who hoard will use public facilities, in order to maintain their personal hygiene and appearance

A person who hoards will typically have poor insight and see nothing wrong with their behaviour and the impact it has on them and others. While there are different ways to categorise people who hoard, some clinicians have attempted to classify hoarding by a person’s level of self-awareness and willingness to respond to an intervention:

| Classification | Description |

| Non-insightful | These people are not co-operative with intervention and many are unwilling to engage in mental health treatment. Intervention by family members or officials may be necessary to initiate action to work toward meeting minimal standards of self-care and sanitation. |

| Insightful but unmotivated | These people recognise there is a problem, but are unwilling or unable to seek help. In some cases, previous attempts at helping have been traumatic so they may become isolated. |

| Insightful and motivated, but non-compliant | These people may want help and seek treatment, but struggle when faced with discarding their possession. |

6.5 How to communicate with someone who hoards

When talking to someone who hoards DO NOT:

- Use judgmental language – like anyone else, adults who hoard will not be receptive to negative comments about the state of their home or their character (e.g. “What a mess!” “What kind of person lives like this?”) Imagine your own response if someone came into your home and spoke in this manner, especially if you already felt ashamed.

- Use words that devalue or negatively judge -people who hoard are often aware that others do not view their possessions and homes as they do. They often react strongly to words that reference their possessions negatively, like “trash”, “garbage” and “junk”.

- Let your non-verbal expression say what you’re thinking – adults with compulsive hoarding are likely to notice non- verbal messages that convey judgment, like frowns or grimaces.

- Make suggestions about the person’s belongings – even well-intentioned suggestions about discarding items are usually not well received by those with hoarding.

- Try to persuade or argue with the person -efforts to persuade people to make a change in their home or behaviour often have the opposite effect.

- Touch the person’s belongings without explicit permission – people who hoard often have strong feelings and beliefs about their possessions and often find it upsetting when another person touches their Anyone visiting the home of someone with hoarding should only touch the person’s belongings if they have the person’s explicit permission.

When talking to someone who hoards DO:

- Imagine yourself in that person’s shoes: how would you want others to talk to you to help you manage your anger, frustration, resentment, and embarrassment?

- Match the person’s language – listen for the individual’s manner of referring to his/her possessions (e.g. “my things”, “my collections”) and use the same language (i.e. “your things”, “your collections”).

- Highlight strengths- all people have strengths, positive aspects of themselves, their behaviour, or even their homes. A visitor’s ability to notice these strengths helps forge a good relationship and paves the way for resolving the hoarding problem (e.g. “I see that you can easily access your bathroom sink and shower,” “What a beautiful painting!”, “I can see how much you care about your cat.”)

- Focus the intervention initially on safety and organisation of possessions, and later work on discarding – discussion of the fate of the person’s possessions will be necessary at some point, but it is preferable for this discussion to follow work on safety and organisation.

Cases show that engagement can often be created through providing practical items such as fridges, heaters or support with welfare benefits. This type of relationship can be accepted more easily, with attention then turning to care of the domestic environment or (often the last to be agreed) personal care. Clearing or cleaning property is more difficult due to the attachment that people often have to their possessions or surroundings. It is necessary to secure the person’s engagement in deciding what should stay and what should go (often better achieved with a more consensual outcome). Recognition should be given to the need to replace what was being given up with forward-looking intervention focusing on lifestyle, companionship and activities.

Coercive interventions can be used sometimes, although the perspectives of people who use services shows that directive approaches are deeply unwelcome and the cost tends to be high in human terms, were extreme. There have been examples of such interventions that, with honest but empathic engagement, positive change can be produced.

7. Clutter Ratings and Guidance for Practitioners

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

| Image rating 1-3 | Image rating 4-6 | Image rating 7-9 |

| Household environment is considered standard.

No Safeguarding referral is needed. If the adult would like some assistance with general housework or feels they are declining towards a higher clutter scale, appropriate referrals can be made subject to age and circumstances. |

Household environment requires professional assistance to resolve the clutter and maintenance issues in the property.

The cases need to be monitored regularly in the future due to risk of escalation or reoccurrence. |

Household environment will require intervention with a collaborative multi agency approach with the involvement from a wide range of professionals. This level of hoarding constitutes a safeguarding concern due to the significant risk to health of the householders, surrounding properties and residents. Residents are often unaware of the implication of their hoarding actions and oblivious to the risk it poses. |

7.1 Image ratings

(Click on the images to enlarge them)

Bedroom clutter image scale:

Kitchen clutter image scale:

Living room clutter image scale:

7.2 Property, structure and garden

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

| All entrances and exits, stairways, roof space and windows accessible. | Only major exit is blocked; Only one of the services is not fully functional (e.g. electric or gas). | Limited access to the property due to extreme clutter;

Evidence may be seen of extreme clutter seen at windows; Evidence may be seen of extreme clutter outside the property. |

| All services functional and maintained in good working order.

Smoke alarms fitted and functional or referrals made to GM Fire and Rescue Service to visit and install. |

Concern that services are not well maintained.

Smoke alarms are not installed or not functioning. Garden is not accessible due to clutter, or is not maintained. |

Services not connected or not functioning properly.

Smoke alarms not fitted or not functioning. Property lacks ventilation due to clutter.

|

| Garden is accessible, tidy and maintained. | Evidence of indoor items stored outside.

Evidence of light structural damage including damp Interior doors missing or blocked open. |

Garden not accessible and extensively overgrown.

Evidence of structural damage or outstanding repairs including damp. Interior doors missing or blocked open. Evidence of indoor items stored outside. |

- Assess the access to all entrances and exits for the property (note impact on any communal entrances and exits). Include access to roof space.

- Does the property have a smoke alarm?

- Visual assessment (non-professional) of the condition of the services within the property e.g. plumbing, electrics, gas, air conditioning, heating, this will help inform your next course of action.

- Are the services connected?

- Assess the garden. Size, access and condition.

7.3 Household functions

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

| No excessive clutter, all rooms can be safely used for their intended purpose.

All rooms are rated 0-3 on the Clutter Rating Scale. |

Clutter is causing congestion in the living spaces and is impacting on the use of the rooms for their intended purpose.

Clutter is causing congestion between the rooms and entrances. Room(s) score between 4-5on the clutter scale. |

Clutter is obstructing the living spaces and is preventing the use of the rooms for their intended purpose.

Room(s) scores 7 – 9 on the clutter image scale. Rooms not used for intended purposes or very limited. |

| No additional unused household appliances appear in unusual locations around the property.

.

|

Inconsistent levels of housekeeping throughout the property.

Some household appliances are not functioning properly and there may be additional units in unusual places. Evidence of outdoor items being stored inside. |

Beds inaccessible or unusable due to clutter or infestation.

Entrances, hallways and stairs blocked or difficult to pass. Toilets, sinks not functioning or not in use. Individual at risk due to living environment. Household appliances are not functioning or inaccessible. No safe cooking environment. Evidence of outdoor clutter being stored indoors stored indoors. No evidence of housekeeping being undertaken. Broken household items not discarded e.g. broken glass or plates. |

| Property is maintained within terms of any lease or tenancy agreements where appropriate;

Property is not at risk of action by Environmental Health |

Property is not maintained within terms of lease or tenancy agreement where applicable. | Property is not maintained within terms of lease or tenancy agreement where applicable.

Property is at risk of notice being served by Environmental Health |

- Can the kitchen be safely used for cooking or does the level of clutter within the room prevent it?

- Select the appropriate rating on the clutter scale. Estimate the % of floor space covered by clutter Estimate the height of the clutter in each room Assess the level of sanitation in the property:

- Are the floors clean?

- Are the work surfaces clean?

- Are you aware of any odours in the property? Is there rotting food?

- Did you see a higher than expected number of flies?

- Are household members struggling with personal care?

- Do any household members lack the mental capacity to make informed decisions about their need for care and support?

- Is there random or chaotic writing on the walls on the property?

- Are there unreasonable amounts of medication collected? Prescribed or over the counter? Is the resident aware of any fire risk associated to the clutter in the property?

7.4 Hoarding and safeguarding

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

| No Concerns for household members | Hoarding on clutter scale 4 -7 doesn’t automatically constitute a Safeguarding Alert. But for hoarding at a scale 5 or more, a referral to the safeguarding adults team should always be considered.

A referral should be made to Bury Council Housing Services if it is a Bury Council property to ensure safety within the home and further support if needed. |

Hoarding on clutter scale 7-9 warrants a Safeguarding Alert. Note if there are any additional concerns for householders. |

- Any properties with children or vulnerable people may require a Safeguarding Alert .

- Take into consideration all aspects of the individual and their surroundings.

- Do any rooms rate 5 or above on the clutter rating scale?

Self-neglect may not be reflected in hoarding, if there are any concerns around a person’s ability to keep themselves safe a safeguarding alert is appropriate. You can always discuss this with Adult Social Care and your manager.

7.5 Animals and Pets

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

| Any pets at the property are well cared for.

No pests or infestations at the property. |

Pets at the property are not well cared for/

Resident is not unable to control the animals; Animal’s living area is not maintained and smells; Animals appear to be under nourished or over fed/

|

Animals at the property at risk due the level of clutter in the property.

Resident may not be able to control the animals at the property. Animal’s living area is not maintained and smells. Animals appear to be under nourished or overfed . Hoarding of animals at the property. |

| Any evidence of mice, rats at the property.

Spider webs in house. Light insect infestation (bed bugs, lice, fleas, cockroaches, ants, etc.) |

Heavy insect infestation (bed bugs, lice, fleas, cockroaches, ants, silverfish, etc.)

Visible rodent infestation. |

- Are there any pets at the property?

- Are the pets well cared for; are you concerned about their health? Is there evidence of any infestation? E.g. bed bugs, rats, mice, etc.

- Are animals being hoarded at the property?

- Are outside areas seen by the adult as a wildlife area?

- Does the adult leave food out in the garden to feed foxes etc.

7.5 Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

| No PPE required No visit in pairs required. | Latex Gloves, boots or needle stick safe shoes, face mask, hand sanitizer, insect repellent. | PPE should include latex gloves, boots or needle stick safe shoes, face mask, hand sanitizer, insect repellent.

Visit in pairs required |

- Following your assessment do you recommend the use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), e.g. protective clothing, at future visits? If so describe what is required.

- Following your assessment do you recommend the resident is visited in pairs? If so indicate why.

8. Agency Actions

8.1 Referring agency

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

| Discuss concerns with the person. | Refer to landlord if resident is a tenant. | Raise Safeguarding Alert within 24 hours. |

| Raise a request to Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service for safety advice. | Refer to Environmental Health. | Raise a request to Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service within 24 hours to provide fire prevention advice. |

| Refer for support assessment if appropriate. | Raise an request to Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service to provide fire prevention advice | |

| Refer to GP if Appropriate. | Provide details of garden services. | |

| Refer to Bury Council Housing Services if Bury Council property. | Refer for support assessment. | |

| Referral to GP. | ||

| Referral to debt advice if appropriate. | ||

| Refer to Animal Welfare services if there are animals at the property. | ||

| Ensure information sharing with all agencies involved to ensure a collaborative approach and a sustainable resolution. |

8.2 Environmental health

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

| No action. | Refer to Environmental Health with details of adult, landlord (if relevant) referrer’s details and overview of problems.

At time of inspection, Environmental Health Officer decides on appropriate course of action. Consider serving notices under Environmental Protection Act 1990, Prevention of Damage By Pests Act 1949 or Housing Act 2004 Consider Works in Default if notices not complied by occupier |

Refer to Environmental Health with details of adult, landlord (if relevant) referrer’s details and overview of problems.

At time of inspection, Environmental Health Officer decides on appropriate course of action. Consider serving notices under Environmental Protection Act 1990, Prevention of Damage By Pests Act 1949 or Housing Act 2004 Consider Works in Default if notices not complied by occupier |

8.3 Social landlords

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

| Provide details on debt advice if appropriate to circumstances. | Visit resident to inspect the property and assess support needs. | Visit resident to inspect the property and assess support needs. |

| Refer to GP if appropriate. | Referral to local Housing Support service to assist in the restoration of services to the property where appropriate. | Attend multi agency Safeguarding meeting. |

| Refer for support assessment if appropriate. | Ensure residents are maintaining all tenancy conditions. | Enforce tenancy conditions relating to residents’ responsibilities. |

| Provide details of support streams open to the resident via charities and self- help groups. | Enforce tenancy conditions relating to residents’ responsibilities. | If resident refuses to engage serve Notice of Seeking Possession under the Housing Act. |

| Ensure information sharing with all agencies involved to ensure a collaborative approach and a sustainable resolution. |

8.4 Practitioners

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

| Provide details on debt advice if appropriate. | Refer to guidance in this Bury Safeguarding Adult Board Hoarding and Self-Neglect Policy. | Refer to guidance in this Bury Safeguarding Adult Board Hoarding and Self-Neglect Policy. |

| Ensure residents are maintaining all tenancy conditions.

|

Ensure information sharing with all agencies involved to ensure a collaborative approach and a sustainable resolution. | Ensure information sharing with all agencies involved to ensure a collaborative approach and a sustainable resolution. |

| Make appropriate referrals for support. | Referral to be made to Bury Council Housing Services for those living in council accommodation.

|

Report concerns within 24 hours to: [email protected]

Tel: 0161 686 8000 Private Sector Rented Enforcement Team if further assistance is required |

| Refer to Housing Association or private landlord. | Contact landlord directly for further assistance and to ensure they are aware of the risk within their property. |

8.5 Emergency services

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

| Ensure information is shared with statutory agencies and feedback is provided to referring agency on completion of home visits. | Ensure information sharing with all agencies involved to ensure a collaborative approach and a sustainable resolution.

Provide feedback to referring agency on completion of home visits. |

Attend Safeguarding multi agency meetings on request.

Ensure information sharing with all agencies involved to ensure a collaborative approach and a sustainable resolution. Provide feedback to referring agency on completion of home visits. |

8.6 Animal welfare

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

| No action unless advice requested | Visit property to undertake a wellbeing check on animals at the property.

Educate client regarding animal welfare if appropriate. Provide advice / assistance with re- homing animals |

Visit property to undertake a wellbeing check on animals at the property.

Remove animals to a safe environment Educate client regarding animal welfare if appropriate. Take legal action for animal cruelty if appropriate. Provide advice / assistance with re-homing animals |

8.7 Safeguarding

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

| No action unless other concerns of abuse are noted. | No action unless other concerns of abuse are noted.

If other concerns of abuse are of concern or have been reported, progression to safeguarding referral and investigation may be necessary. |

Safeguarding alert should be made |

Engagement can often be created through the provision of practical items such as fridges, heaters or support with welfare benefits. This type of relationship can be accepted more easily, with attention then turning to care of the domestic environment or (often the last to be agreed) personal care. Clearing or cleaning property is more difficult due to the attachment that people often have to their possessions or surroundings. It is necessary to secure the individual’s engagement in deciding what should stay and what should go (often better achieved with a more consensual outcome). Recognition should be given to the need to replace what was being given up with forward-looking intervention focusing on lifestyle, companionship and activities.

Direct interventions along with an honest and empathic approach can produce positive change.

9. Choice and Consent

In relation to health and social care, consent is the process by which an adult agrees for a professional to provide care. Consent may be given, verbally, non-verbally or in writing.

For the consent to be valid, the adult must:

- Be competent to make the particular decision;

- Have received sufficient information to inform the decision;

- Not be acting under duress.

The practitioner must ensure that the person is kept central to any decision undertaken when a concern is being raised. There are recognised exceptions to gaining consent for action in relation to a safeguarding concern:

- When a person is deemed to lack mental capacity and a best interest decision is required.

- When a person is acting under duress / undue influence.

- When it is in the public interest and/or there are legal restrictions because a crime has or will be committed.

10. Assessing Mental Capacity and Recognising Fluctuating Capacity

See also Mental Capacity chapter.

- An early assessment of the person’s mental capacity is essential.

- A person must be assumed to have mental capacity unless it is established that they do not.

- When people are being supported to make their own decisions – every effort should be made to encourage and support them to make the decisions for themselves. If lack of mental capacity is established, it is still important to involve the person as far as possible in making decisions.

- Capacity can fluctuate, so if you see signs of change then you should assess capacity again;

- If the person has mental capacity and is making unwise decisions, you must respect their decisions but can still offer support and guidance.

- If a person has compromised mental capacity and they are non-engaging, it may take a while to assess the full extent of their cognitive impairment.

- If the person lacks the mental capacity to make informed decisions about risk, all involved parties must act in their best interests – and all best interest decisions must be fully documented (see also Best Interests chapter).

- Consider the less restrictive option. Someone making a decision or acting on behalf of a person who lacks mental capacity must consider whether it is possible to decide or act in a way that would interfere less with the person’s rights and freedoms of action, or whether there is a need to decide or act at all.

- A n advocate can help an individual be involved in decisions about their care and support.

11. Other Considerations

| Is there anything causing you concern of immediate high risk or danger? | Has a crime been committed? | What are the person’s views and wishes? |

| Assess if they have mental capacity and if they have had a capacity assessment check when the decision was made. | Carry out property inspections.

The Fire and Rescue Service or Housing services may be able to assist you. |

Look into welfare benefits. Are they in receipt of any? Have they had any breaks in their benefits? |

| Find out who owns their property. Are they a home owner or is there a private landlord or social landlord? | Check for hospital admissions | Carry out risk assessments (safeguarding) |

| Other than friends and family is there anyone the person engages with. Where do they get their groceries? Are there any places they often visit? | Liaise with other key services including but not limited to health, police, social care, housing, and care agencies etc. | Have they received any interventions for self-neglect before? |

| Take a visual audit. Try to remember how they physically looked and how was the appearance of the home? | Check medications and medical history consider mental health, learning disability, brain injury or physical illness | Look at the persons financial history or speak to them about any financial concerns they may have. Are they in any arrears? |

| How long have they been self- neglecting? | Is the self-neglect impacting anyone else? | Are there any animals in the property, if so are they being well cared for? |

| If there is anyone else living in the household? Do they have any involvement with statutory services? | Is the home stocked with enough food and the right kind of food? | Are all the amenities working in the home, such as water and electric? |

| Is there evidence of frequent attention from services or repeated failure to attend appointments? | Check all records you have available to you. | Does the person have any cultural or religious requirements? |

| Speak to family, friends and neighbours about any concerns they may have. | Does the person have any issues with substance misuse? | Ask them their preferred communication method. |

12. Advocacy and Support

See also Independent Advocacy

Under the Care Act 2014, the role of an independent advocate is to ensure the person’s voice is heard and their rights are upheld. They also enable the person to be fully involved in the process and in decision-making. This can include representing someone if they are unable to represent themselves and can also include supporting someone to self-advocate. There is duty upon the local authority to arrange an independent advocate. Bury has commissioned Ncompass.

This duty applies in cases where, if an independent advocate was not provided, the person would have substantial difficulty in being fully involved and there is no appropriate individual available who meets the criteria of the Care Act.

The duty applies to both carers and those with care and support needs across different types of care setting.

The duty to arrange an independent advocate applies from first contact onwards, in the care planning process, and in a review of arrangements. If the person moves area, the local authority carrying out the assessment, planning or review is responsible for deciding whether continuity of independent advocacy is desirable.

Professionals make a judgement whether a person has substantial difficulty; they do not have to prove this conclusively.

A carer, friend or family member can be appointed to assist a person’s involvement by acting as an ‘appropriate individual’, instead of appointing an independent advocate. They must meet the criteria of the Care Act and be able to maximise the individual’s involvement in the process. There are instances when a person may be judged as not being an appropriate individual or where they may not be able and willing to provide the right support.

Being an independent advocate means maximising the individual’s involvement, supporting and representing the person to:

- understand key care and support or safeguarding processes, communicate views, wishes and feelings, and self-advocate where possible.

- understand and uphold their rights.

- understand how their needs can be met in the local context.

- make decisions, and challenge decisions where the advocate believes that they don’t fulfil the local authority’s duty to promote individual wellbeing.

13. Public Health Act 1936

Section 79: Power to require removal of noxious matter by occupier of premises – the Local Authority (LA) will always try and work with a householder to identify a solution to a hoarded property, however in cases where the resident is not willing to co-operate the LA can serve notice on the owner or occupier to “remove accumulations of noxious matter‟. Noxious not defined, but usually is “harmful, unwholesome‟. No appeal available. If not complied with in 24 hours, The LA can do works in default and recover expenses.

Section 83: Cleansing of filthy or verminous premises – where any premises, tent, van, shed, ship or boat is either;

- Filthy or unwholesome so as to be prejudicial to health; or

- Verminous (relating to rats, mice other pests including insects, their eggs and larvae)

LA serves notice requiring clearance of materials and objects that are filthy, cleansing of surfaces, carpets etc. within 24 hours or more. If not complied with, Environmental Health (EH) can carry out works in default and charge. No appeal against notice but an appeal can be made against the cost and reasonableness of the works on the notice.

14. Escalation Process

When working with children, adults and families, there may be times when professionals disagree with each other’s decisions, which may result in the need to escalate concerns about particular cases. Escalation is a positive and healthy part of good practice for working with children and adults and is open to everyone.

Practitioners working with people who often present with complex needs can have different opinions and views on the best way to provide support. Discussion and debate with colleagues, along with constructive challenge should be an integral part of our everyday practice.

At times there may be disagreements about:

- Thresholds;

- The appropriate course of safeguarding actions.

There may also be concerns about professional practice. Practitioners have a responsibility to:

- speak to managers about any disagreements; or

- ask to speak to the manager of the person the disagreement is with and if necessary, keep going up the hierarchy if it is felt opinions are not being understood.

See Multi Agency Escalation Process for more information.

15. Checklist for staff

- Is the person physically frail or has a physical disability, learning disability, mental health needs, long term condition or misuses substances or alcohol?

- Does the person have capacity to make decisions about their health, care and support needs?

- Has a formal mental capacity assessment been undertaken? If the person lacks capacity to understand they are self- neglecting has a best interest meeting taken place?

- Is the person unwilling or failing to perform essential self-care tasks?

- Is the person living in unsanitary accommodation possibly squalor?

- Is the person unwilling or failing to provide essential clothing, medical care for themselves necessary to maintain physical health, mental health and general safety?

- Is the person neglecting household maintenance to a degree that it creates risks and hazards?

- Does the person present with some eccentric behaviour and do they obsessively hoard and is this contributing to the concerns of self-neglect?

- Is there evidence to suggest poor diet or nutrition g. very little fresh food in their accommodation/mouldy food identified?

- Is the person declining prescribed medication or health treatment and/or social care staff in relation to their personal hygiene and having a significant impact on their wellbeing?

- Is the person declining or refusing to allow access to healthcare and/or social care staff

- Is the person refusing to allow access to other agencies or organisations such as utility companies, fire and rescue, ambulance staff, housing or landlord?

- Is the person unwilling to attend appointments with relevant health or social care staff?

- Have interventions been tried in the past and not been successful?

- Has the person any family, partners or friends that may be able to assist with any interventions?

- Is the perceived self-neglect impacting on anyone else for example family members, partners, neighbours, etc.

- Are there dependent children living in the accommodation?